Until recently, progressive neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as acute brain injuries like stroke were thought to result in an irreversible loss of neurons with no possibility of neuronal regeneration. In the last few years, this belief has been challenged by numerous studies that have demonstrated that specialized areas of the brain retain pluripotent precursors with the capacity to regenerate neurons in adult mammals such as rodents1-3, non-human primates4, and humans5,6. The function of neurogenesis in the adult brain is still unknown, and we are far from understanding the processes regulating it. The available knowledge indicates that significant limitations at all key steps in the process will have to be overcome to achieve functionally relevant replacement of lost brain networks from endogenous neuronal stem cells. However, that new neurons are added continously to the adult brain is a discovery that has already changed the way we think about neurobiology and may soon change the way we understand and approach neurodegenerative diseases.

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common dementing disorder, is a remarkably pure cognitive impairment7 whose anatomical hallmarks are the so-called amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and a profound loss of synapses and neurons in the brain. Cognitive impairment in AD can be attributed to the loss of specific populations of neurons and the breakdown of vulnerable brain networks, particularly those involved in memory formation. Mutations associated with familial AD have been mapped to the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene or to genes whose products participate in the proteolytic processing of the APP protein8. Familial forms of AD have early onset and progress to moderate and severe stages in a relatively short time. Sporadic AD, which has a later age of onset, accounts for 98 % of cases and varies considerably in its rate of progression. The underlying pathogenic processes, however, are thought to be shared by both forms of the disease. Proteolytic processing of APP gives rise to amyloid  (A

(A a peptide which aggregates into insoluble amyloid plaques. The hypothesis that has dominated the field for the last 15 years proposes that the accumulation of A

a peptide which aggregates into insoluble amyloid plaques. The hypothesis that has dominated the field for the last 15 years proposes that the accumulation of A and the deposition of amyloid plaques is the main cause for the toxicity observed in AD. This hypothesis, however, has been questioned by a number of recent studies showing that the level of soluble A

and the deposition of amyloid plaques is the main cause for the toxicity observed in AD. This hypothesis, however, has been questioned by a number of recent studies showing that the level of soluble A , but not the degree of A

, but not the degree of A deposition, correlates with functional impairment in humans9, and that synaptic anatomical and functional deficits occur much before A

deposition, correlates with functional impairment in humans9, and that synaptic anatomical and functional deficits occur much before A deposition in humans10,11 and in transgenic mouse models12,13. Furthermore, we have shown that AD-like pathology in transgenic mice can be independent of the accumulation and deposition of A

deposition in humans10,11 and in transgenic mouse models12,13. Furthermore, we have shown that AD-like pathology in transgenic mice can be independent of the accumulation and deposition of A 14. In humans, a decrease in synaptic density number is the strongest correlate to degree of cognitive impairment10,11,15,16. These observations strongly suggest that plaque deposition may be secondary to functional deficits, and that soluble A

14. In humans, a decrease in synaptic density number is the strongest correlate to degree of cognitive impairment10,11,15,16. These observations strongly suggest that plaque deposition may be secondary to functional deficits, and that soluble A and possibly other factors in addition to A

and possibly other factors in addition to A accumulation have a crucial role in the early pathogenesis of the disease.

accumulation have a crucial role in the early pathogenesis of the disease.

At its earliest clinical phase, AD manifests itself as an amnestic mild cognitive impairment (or minimal cognitive impairment, MCI) whose identification poses a considerable challenge to the clinician17. The impairment may affect any or a number of memory functions. In those individuals who will progress to AD, MCI evolves into the so-called prodromal phase which is characterized by a further progressive deterioration of memory functions which may interfere with normal social functioning. Other forms of cognitive impairment such as language disorders and impaired visuospatial learning skills and executive functions are added over the course of several years after diagnosis, and changes at these stages frequently involve profound alterations in personality. Eventually, patients progress into clinical dementia in which many brain functions are affected. Definitive diagnosis, however, is possible only at the time of autopsy, when the co-occurrence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), and particularly of NFTs in the neocortex, are indicative of AD when consistent with the individual’s clinical history.

The regions of the brain that are most affected at the early stages of the disease are the associative cortexes, particularly the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex, which are thought to have a fundamental role in associative memory functions and in spatial contextual memory encoding18,19. At early stages, the circuits affected are fundamentally glutamatergic and cholinergic, consistent with damage to the septal-hippocampal and basal forebrain-neocortical pathways and their projection neurons20. Olfactory dysfunction is a feature that sometimes accompanies preclinical AD and it has been proposed that it may serve as a predictor of the development of cognitive symptoms21-23. As the disease progresses, other cortical regions are affected, involving at first high-order association regions much more frequently than the primary motor and sensory regions. At later stages in the progression of the disease, the loss of medium-sized pyramidal neurons effecting corticocortical connections, together with neurons throughout the cerebral cortex, add other spheres of cognitive impairment such as language disorders, impaired visuospatial skills and executive functions to the gradual memory loss as the disease progresses into its moderate and severe stages17.

APP is an integral membrane protein that is axonally transported to nerve terminals and accumulates at presynaptic sites24,25. APP’s transmembrane region contains the carboxyterminal portion of the A peptide, flanked by a short intracytoplasmic C-terminal domain and a much larger extracellular domain at its N-terminus. Proteolytic processing at the proximal region of the extracellular domain and within the transmembrane region by

peptide, flanked by a short intracytoplasmic C-terminal domain and a much larger extracellular domain at its N-terminus. Proteolytic processing at the proximal region of the extracellular domain and within the transmembrane region by

,

,

-secretases gives rise, in different combinations, to the soluble extracellular domain, the poorly soluble A

-secretases gives rise, in different combinations, to the soluble extracellular domain, the poorly soluble A 1-42 (as well as A

1-42 (as well as A 1-40), the soluble p3 peptide and a 99-amino acid carboxyterminal fragment as major cleavage products26,27. The cytosolic region of APP has a caspase recognition site at Asp 664 that generates a cytotoxic 31-amino acid C-terminal fragment, C3128-33 This peptide encompasses a YENPTY clathrin-pit internalization signal34 that acts as a binding site for several APP-interacting proteins35-41. Accumulating evidence suggests that the intracellular carboxy (C)-terminus of APP is involved in multiple cellular processes35,40,41 and our studies have implicated it directly in the pathogenesis of the AD-like phenotype in transgenic mice14.

1-40), the soluble p3 peptide and a 99-amino acid carboxyterminal fragment as major cleavage products26,27. The cytosolic region of APP has a caspase recognition site at Asp 664 that generates a cytotoxic 31-amino acid C-terminal fragment, C3128-33 This peptide encompasses a YENPTY clathrin-pit internalization signal34 that acts as a binding site for several APP-interacting proteins35-41. Accumulating evidence suggests that the intracellular carboxy (C)-terminus of APP is involved in multiple cellular processes35,40,41 and our studies have implicated it directly in the pathogenesis of the AD-like phenotype in transgenic mice14.

The most abundant cleavage of APP in non-pathological conditions is by  -secretase within the A

-secretase within the A sequence8. This cleavage releases the soluble ectodomain of APP, sAPP, which is present in brain tissues and in cerebrospinal fluid and has been shown to enhance synaptogenesis, neurite outgrowth, cell adhesion and cell survival42. Even though the processes involved in the generation of A

sequence8. This cleavage releases the soluble ectodomain of APP, sAPP, which is present in brain tissues and in cerebrospinal fluid and has been shown to enhance synaptogenesis, neurite outgrowth, cell adhesion and cell survival42. Even though the processes involved in the generation of A through cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) are being elucidated, the function of APP and that of A

through cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) are being elucidated, the function of APP and that of A remain unclear. APP is a member of a family of proteins that includes the amyloid precursor-like protein 1 (APLP1) and 2 (APLP2)43,44. Whereas APP null mice show relatively mild brain abnormalities45, the APP, APLP2 double knockout has a lethal phenotype46 suggesting a fundamental role for the APP family and functional redundancy between APP and the APLPs in mammalian development.

remain unclear. APP is a member of a family of proteins that includes the amyloid precursor-like protein 1 (APLP1) and 2 (APLP2)43,44. Whereas APP null mice show relatively mild brain abnormalities45, the APP, APLP2 double knockout has a lethal phenotype46 suggesting a fundamental role for the APP family and functional redundancy between APP and the APLPs in mammalian development.

Until recently, a central assumption in neuroscience had been that new neurons do not arise in the adult mammalian brain. This had been the accepted belief47 since the idea was proposed by Ramon y Cajal48 and others at the beginning of the last century. This view firmly prevailed in spite of sporadic reports that showed that new cells could arise in certain specialized areas of the brain49-54. The thorough historical review by C.G. Gross55 provides an illuminating example of a ‘paradigm shift’56 and shows how the weight of authority and the engraftment of a ruling belief in a field can completely block discovery and make researchers blind to the evidence for almost a century. About ten years ago, studies that firmly established that new neurons are continuously born in the adult mammalian brain57,58 including non-human primates4 and humans5,6 were published59,60. It is now widely accepted that undifferentiated neural stem/progenitor cells (NPCs) are maintained in specialized microenvironments or ‘niches’ in some brain regions61 in which these cells may undergo symmetrical division at a very low rate62,63 maintaining their multipotency, or alternatively undergo asymmetric division to differentiate into neuronal precursors. In rodents, it was shown that neurogenic stem cells are concentrated in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle wall3 and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (SGZ) of the hippocampus64. Cells born in the SVZ during adult life travel anteriorly through the rostral migratory stream along tubular structures formed by astrocytes that envelop the neuronal progenitors into the olfactory bulb (OB), where they differentiate into interneurons65. This process is referred to as “chain migration”57. Cells born in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus migrate a short distance to integrate in the granular layer60.

Together with the dethronement of the paradigm of ‘brain constancy’, the ‘neurocentric’ view of the brain is also being reconsidered. The fundamental role of glia in the adult brain was further underscored by the studies of Alvarez-Buylla and coworkers57 and other groups66 that demonstrated that astrocytes in the SVZ and SGZ are neurogenic stems cells in mammals67 and that radial glia function as progenitors for the majority of mammalian CNS neurons66. The neurogenicity of SVZ and SGZ progenitors in the adult mammal brain is restricted by signals from their local tissue environment, as astrocytes outside these zones do not show neurogenic properties in vivo61. Highlighting the importance of cues from their microenvironment, transplantation experiments demonstrated that SVZ cells loose their neurogenic potential when placed into non-neurogenic regions of the brain61. Thus, groups of astrocytic cells both contain neural progenitors and participate in the creation of the microenvironment that stimulates neurogenesis61,66. Not surprisingly, well-established developmental signal molecules and morphogens such as Notch, BMPs, Noggin and sonic hedgehog have been implicated in the maintenance of these adult neurogenic microenvironments68 that involve endothelial cells69.

That neural stem/progenitor cells also exist in adult primate and human brain has now been firmly established4,6,70,71 for the subependymal zone72 and for the hippocampus5,73. Sanai et al.74 described an astrocyte band along the lateral ventricles of adult human brains ages 19-68 years that had not been described in other mammalian species. Although explant cultures of adult human SVZ astrocytes could produce multipotent, self-renewing neurospheres both in the presence and in the absence of exogenously added growth factors, no evidence of chain migration could be found in the SVZ or in the human olfactory peduncle in this study. The substantial loss of functional olfactory receptor genes in the human genome when compared to rodents suggests that the sense of smell in humans has long lost part of its adaptive value. Consistent with this idea, the rostral migratory stream that continues to supply replacement interneurons to the rodent olfactory bulb is weak or undetectable in humans, possibly reflecting the reduced functionality of the human OB. A recent report by Bedard and Parent75, however, reported the presence of cells expressing cell cycle markers and markers for immature neurons in the human olfactory bulb (OB), suggesting that precursor proliferation may also occur, albeit at a much reduced rate, in this region of the adult human brain. In contrast, the dentate gyrus and the hilus in cornus ammonis 4 region (CA4) of the human hippocampus are possibly the most active areas of progenitor proliferation in adult primates76,77 and humans5.

In a seminal paper, Eriksson et al.5 examined hippocampal sections of non-metastatic cancer patients that had received bromo-deoxyuridine (BrdU) as part of their treatment. This study revealed a relatively high percentage of proliferating progenitors (as evidenced by BrdU incorporation in their DNA) in the granular cell layer and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus and in CA4. Remarkably, and albeit the sample number precluded drawing quantitative conclusions, the highest number of proliferating precursors in the granule cell layer and in the hilus were found in human adults of middle and advanced age. Other studies have shown a decrease in the levels of adult progenitor proliferation with increasing age in rodents, but a stronger response to its stimulation when compared to young hippocampus78.

The function of adult neurogenesis is still not known. In 2001, however, Shors et al. demonstrated that performance of a hippocampus-dependent learning task was dependent on the presence of replicating progenitors, suggesting that neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus has a role in learning memory79. The number of new cells generated in the hippocampus of rat is in the order of the thousands per day80 and a high proportion of them differentiate into neurons81,82. However, only about half of these newly generated neurons will survive after the first few weeks83,84. Those that survive seem to integrate into preexisting hippocampal circuits and may permanently replace granule cells born during development84. Survival of new neurons is significantly enhanced by exposure to hippocampal-dependent learning tasks84,85, by environmental enrichment, and by running86. Most remarkably, production overweights loss of proliferating progenitors in the rat hippocampus such that neuronal cell numbers increase continously throughout life87. A central idea that long supported the assumption of ‘cerebral constancy’ was the proposed need for the organism to preserve memories of experiences throughout a relatively long lifespan; however, a fundamental feature of memory is that it is selective, so that not all memories are preserved, and those that are preserved are not static but are reprocessed continously in a dynamic fashion88. Moreover, a memory is associated with a pattern of activation88, not with an individual neuronal circuit in its physical sense. Thus, the preservation of memories may not necessarily require the preservation of individual neurons.

A recent study by Deiseroth et al.89 has addressed for the first time the question of whether activity and neurogenesis are coupled, a process that would implement a form of network plasticity that would be conceptually analogous to the well-known forms of plasticity at the synaptic level, but occurring at the cellular network level89. Using an in vitro model, the authors demonstrated that excitatory stimuli act directly on adult hippocampal proliferating NPCs to favour adoption of the neuronal phenotype. The generation of new neurons was strongly dependent on Cav1.2/1.3 type of HVA channels and on NMDA receptor activity. These in vitro results strongly suggest excitation-neurogenesis coupling, and are consistent with a proposed model for frequent memory turnover in the hippocampus, a critical locus for temporary memory storage90,91. Indeed, organismal-level stimuli that entail an increase in neuronal activity such as learning85,92, exposure to environmental enrichment86,93, and voluntary running86 have been shown to stimulate neurogenesis and enhance the survival of new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. Although neither of these behavioral interventions increase adult neurogenesis in the SVZ/OB93, proliferation in these areas can be influenced by olfactory sensory stimuli94. These observations strongly suggest a need for local network activity for the stimulation of neurogenesis and the survival of differentiated progenitors94. Thus, neurogenesis may have a role in plasticity at a cellular network level89 in a manner that is in turn regulated by activity-induced excitation of those networks.

Acute injury, such as hipoxia following middle artery occlusion in rat, induces the proliferation of neuronal precursors after extensive damage has occurred as consequence of infarctum in the striatum and parietal cortex95. These new neurons are generated in the SVZ and tend to migrate towards the site of the lesion. It has been proposed that the migration of precursors is guided by a migration-inducing activity produced by astrocytes at the ischemic site96. Only a small fraction of the cells generated in the initial proliferative response, however, survives 6 weeks after the insult95 and it is not clear how or if these cells can contribute to functional recovery of neuronal networks. However, recent studies97-99 showed that stimulation of NPC proliferation and possibly survival may be enhanced by growth factors even in older rodents99, suggesting that the endogenous neurogenic response to acute injury could in principle be modulated exogenously. In agreement to the findings by Eriksson et al. for endogenous neurogenesis in human brains5, the responsiveness of aged mouse brains to growth factor-stimulated neurogenesis was comparable to that of young animals, even when the overall level of endogenous neurogenesis in older mice were decreased. Neurogenesis following acute injury, however, has in most cases been described for regions close to the SVZ, suggesting that the SVZ preferentially contributes new neurons to the lesioned area by activation and migration of its progenitors, with a much smaller contribution of progenitor cells from the damaged area itself or from other regions of the brain. A variety of other forms of acute brain injury, such as mechanical lesions, elicit similar effects on the proliferation of neuronal precursors100.

The activation of neurogenic processes as a response to chronic damage is much less well documented. In most cases of activation of neurogenesis as a response to injury, the origin of the proliferating precursors can be traced to the SVZ and the SGZ in the dentate gyrus. However, other regions of the brain for which endogenous multipotent precursors have not been described, such as the postnatal mouse cortex, have been found to respond to injury with the proliferation of endogenous neural precursors as well101. Targeted photolytical degeneration of corticothalamic neurons in layer VI of anterior cortex in adult mice activated the production of new neuronal cells that could form appropiate long-distance corticothalamic connections101. In contrast to the massive losses of cells that generally accompany acute injury, only 20% of the total number of neurons in the treated area were targeted in these experiments. Thus, the induction of de novo neurogenesis in areas of the brain in which it does not normally occur may follow the induction of a synchronous “neurodegenerative-like” lesion.

|

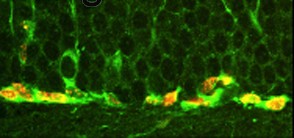

Figure 1. Bromodeoxyuridine-labeled nuclei (red) of cells expressing the immature neuronal marker doublecortin (DCX) (green) in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus of mice that model Alzheimer’s disease. |

Supporting the idea that slow damage as that leading to neurodegeneration may also induce progenitor proliferation, we have described higher numbers of replicating neuronal progenitors in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus of transgenic mice that model AD102 (Figure 1). This is in contrast to prior findings from different transgenic mouse models of AD in which transgenic mice showed impaired, rather than increased, neurogenesis103-105. These disparities raise the possibility that different forms of AD may differ with respect to their association with neurogenesis, especially when considering that sporadic AD accounts for the great majority of the cases and is thought of as a heterogeneous disorder. Supporting our observations in transgenic mouse models, Jin et al. recently demonstrated that increased levels of neuronal progenitors expressing high levels of markers of immature neurons could also be found in the dentate gyrus and in the CA1 regions of the hippocampus of human AD patients when compared to age-matched normal controls106. These results suggest that proliferation of neuronal precursors may take place in aged patients with AD and that this process may be exacerbated by the ongoing neurodegenerative process. The evidence for de novo neurogenesis induced by chronic injury, however, is far from being definitive.

That the two regions that remain ostensibly neurogenic in the adult brain are part of the structures supporting higher-level functions affected at the early stages of AD (olfaction and associative memory) may be interpreted as pointing out to deficits in endogenous neurogenesis as a contributing factor in the early pathogenesis of the disease. This may suggest that sporadic AD may have a component of insufficient neurogenic replacement or insufficient neurogenic stimulation. This view is consistent with epidemiological data suggesting that higher education and increased participation in intellectual, social and physical aspects of daily life are associated with slower cognitive decline in healthy elderly and may reduce the risk of AD107. These aspects of life experience have been dubbed “cognitive reserve” as they seem to point out not to a specific decrease in anatomical pathology but to a higher tolerance to such pathology.

Some studies in AD brains106 and in mouse models of AD102, however, revealed increased, not decreased, levels of dividing neuronal progenitors. That we observed increased neurogenesis in young animals, at ages well before the onset of overt pathology and in the absence any detectable increase in cell death13, suggests that synaptic abnormalities in transgenic mice may be sufficient to stimulate neurogenesis102. Synaptic loss is possibly the earliest anatomical deficit detectable in the progression to AD. The number of presynaptic objects present in frontal cortex of mildly impaired patients is decreased by 25% with respect to age-matched controls10,15, and the degree of synaptic loss is more robustly correlated to cognitive impairment than any other morphological indicator in the disease (number of plaques or tangles, degree of neuronal perykaryal loss, or extent of cortical gliosis)7. Whether changes in rates of progenitor proliferation occur in brains of MCI or early AD patients is still not known; studies aimed to answer this question should provide valuable information as to whether synaptic deficits in early AD might also be sufficient to stimulate neurogenic processes.

At first glance, the recent findings of coupling between excitation and neurogenesis seem to be at odds with the observed decrease in the number of synapses early in the pathogenesis of AD, which would be expected to result in a decrease in overall network activity. However, as suggested by the studies of Deiseroth et al., the activity-dependent proliferative bursts of progenitors in the hippocampus precede the excitation-induced bias for the choice of neuronal fates, which is dependent on NMDA receptor activity in vitro89. It has been proposed that while excess glutamate will be toxic to established, mature neurons, differentiating neuronal precursors will respond to this stimulus by the production of new neurons89. If, as it has been proposed108 and the available AD data suggest102,106, the loss of small numbers of mature neurons or a decrease in the numbers of presynaptic terminals signal the proliferation of neuronal precursors, then the increased levels of dividing neuronal precursors found in AD brains and in mouse models of AD are likely to represent the response of the local network to these synaptic alterations. However, even though progenitor proliferation might be activated by synaptic deficiencies, their survival heavily depends on function89,92. Moreover, the proportion of surviving progenitors that will adopt a neuronal fate is also dependent on their integration in circuits with active excitatory synaptic connections. Notwithstanding these caveats, that the neurogenic response remains functional in the framework of ongoing neurodegeneration is encouraging for the prospects on intervention.

The ultimate requirement for neurogenesis to be beneficial in the adult is that it contributes to function at the systemic level according to the cognitive and psychological definition of function109. The different levels of analysis in adult neurogenesis have been adequately described by Kempermann et al.109, and we refer the reader to this review for further information. All available evidence indicates that continous hippocampal neurogenesis may be involved in learning92,110. It is possible that increases in continuous neurogenic processes may be activated by relatively ‘mild’ injuries such as a decrease in synaptic numbers, as it appears to be the case in transgenic mice102. If this is also true in early AD, an unique window of opportunity may exist in which neurogenesis could potentially be tapped on to contribute to functional ‘repair’ of the adult brain. However, many factors are required for neurogenic processes to contribute to function. Survival and acquisition of a neuronal phenotype by NPCs are dependent not only on network activity, but also on the existence of a complete environment capable of supporting survival, maturation and function by the production of neurotrophins and other regulators of proliferation and differentiation111-114. When the network structures in which NPCs can integrate are compromised, increased proportions of proliferating progenitors may die. If death of moderate numbers of cells can activate neurogenesis101, increased numbers of dying precursors may signal further activation of NPC proliferation. Would ongoing neurogenic processes contribute to ‘repair’ at all stages in AD, or might there be a requirement for a minimal degree of integrity of the network structure for neurogenesis to be beneficial? It is conceivable that a temporal distinction exists in the role of neurogenesis during the course of a slow degenerative disease, one dictated by the degree of permissibility of the environment in which the process is taking place.

The processes that underlie the initial loss of functional synaptic elements early in the progression to AD are not known. The “amyloid hypothesis”, which has considerable experimental support, states that increases in the amounts of low and high order oligomers of the A peptide released by proteolytic cleavage of APP can induce deleterious processes at the cellular and network level. Unfortunately, the investigation of the biological role of A

peptide released by proteolytic cleavage of APP can induce deleterious processes at the cellular and network level. Unfortunately, the investigation of the biological role of A has long been out of the main focus of interest, possibly as a consequence of a widespread misconception of A

has long been out of the main focus of interest, possibly as a consequence of a widespread misconception of A as a wholly undesirable endogenous “toxin”. Consistent with its presence at synaptic sites, however, many studies have suggested a role of oligomeric A

as a wholly undesirable endogenous “toxin”. Consistent with its presence at synaptic sites, however, many studies have suggested a role of oligomeric A in the modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in vivo115-120 and all amyloidogenic A

in the modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in vivo115-120 and all amyloidogenic A peptides have been reported to enhance Ca2+ entry or destabilize intracellular Ca2+ storage8,42,121,122. Moreover, Kamenetz et al. recently showed that neuronal activity can be regulated by A

peptides have been reported to enhance Ca2+ entry or destabilize intracellular Ca2+ storage8,42,121,122. Moreover, Kamenetz et al. recently showed that neuronal activity can be regulated by A and in turn regulate the production and secretion of A

and in turn regulate the production and secretion of A by controlling the proteolytic processing of APP123. Their observations strongly indicate on a role of A

by controlling the proteolytic processing of APP123. Their observations strongly indicate on a role of A as a negative feedback regulator of neuronal activity and it is thus conceivable that alterations in this feedback process may result in increased A

as a negative feedback regulator of neuronal activity and it is thus conceivable that alterations in this feedback process may result in increased A levels, decreased local network activity, and a decrease in numbers of functional synaptic sites, which may in turn further decrease network activity.

levels, decreased local network activity, and a decrease in numbers of functional synaptic sites, which may in turn further decrease network activity.

On the other hand, the soluble secreted derivatives generated when APP is cleaved by  -secretase on the pathway to A

-secretase on the pathway to A generation and by

generation and by  -secretase in the non-amyloidogenic pathway (

-secretase in the non-amyloidogenic pathway ( -sAPP and

-sAPP and  -sAPP respectively), that encompass APP’s extensively glycosylated ectodomain, have been implicated in the enhancement of synaptogenesis, neurite outgrowth, cell survival and cell adhesion42, and recently in the modulation of neurogenesis in the SVZ124. Thus APP may serve two separate functions, one possibly local at synaptic sites and another one at the network/system level through the action of sAPP as a survival/neurogenic factor. Interestingly, a recent report has suggested that aggregated A

-sAPP respectively), that encompass APP’s extensively glycosylated ectodomain, have been implicated in the enhancement of synaptogenesis, neurite outgrowth, cell survival and cell adhesion42, and recently in the modulation of neurogenesis in the SVZ124. Thus APP may serve two separate functions, one possibly local at synaptic sites and another one at the network/system level through the action of sAPP as a survival/neurogenic factor. Interestingly, a recent report has suggested that aggregated A 1-42 may also have a neurogenic effect in fate choice of NPCs in culture125.

1-42 may also have a neurogenic effect in fate choice of NPCs in culture125.

It is likely that continuing neurogenesis has a function in plasticity at the local network and system levels in the adult brain. To the extent that neurogenesis may contribute to function in the adult human CNS, the process does not suffice to preserve function when injury or degenerative processes have ensued. The observation that the mildest form of impairment in new memory formation is correlated with a considerable decrease in synapse number in humans10 may suggest that during the latent phase, ongoing pathological processes such as an increase in A levels may be tolerated by local neuron/glial networks. If we make the assumption that changes in connectivity that are below ~25% can be absorbed without an overall effect on high-order functions, it is reasonable to expect that interventions before or at those stages will be most effective to prevent further, more drastic changes. The potential for stem-cell derived transplantation therapy as a possible intervention has been the focus of intense research in the last years. We refer the reader to the article by Lindvall et al126 for a comprehensive review on this subject. The use of endogenous sources for cell replacement, however, offers several key advantages such as the absence of ethical concerns and the avoidance of immunological reactions. A thorough consideration of the challenges to the design of treatment strategies based on the stimulation of endogenous neurogenesis for replacement of affected networks, mainly centered on the delivery of growth factors, can be found in the review article by Lie et al127.

levels may be tolerated by local neuron/glial networks. If we make the assumption that changes in connectivity that are below ~25% can be absorbed without an overall effect on high-order functions, it is reasonable to expect that interventions before or at those stages will be most effective to prevent further, more drastic changes. The potential for stem-cell derived transplantation therapy as a possible intervention has been the focus of intense research in the last years. We refer the reader to the article by Lindvall et al126 for a comprehensive review on this subject. The use of endogenous sources for cell replacement, however, offers several key advantages such as the absence of ethical concerns and the avoidance of immunological reactions. A thorough consideration of the challenges to the design of treatment strategies based on the stimulation of endogenous neurogenesis for replacement of affected networks, mainly centered on the delivery of growth factors, can be found in the review article by Lie et al127.

Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) has neuroprotective and neurogenic effects128 and it has been shown that peripheral infusion of IGF-I can increase NPC proliferation, selectively induce neurogenesis129, and ameliorate the age-related decline in hippocampal neurogenesis in rats130. Moreover, a comprehensive study by Carro et al.131 demonstrated that serum IGF-I modulates A levels in brain. IGF-I treatment dramatically reduced A

levels in brain. IGF-I treatment dramatically reduced A burden in rats and transgenic mice modelling AD131, suggesting that IGF-I signaling may also have a direct role the pathogenesis of AD132.

burden in rats and transgenic mice modelling AD131, suggesting that IGF-I signaling may also have a direct role the pathogenesis of AD132.

Providing evidence that modulation of the endogenous progenitor cell response to injury may be beneficial for recovery after injury, Nakatomi and colleagues showed that intraventricular infusion of FGF-2 and EGF after selective degeneration of CA1 pyramidal neurons in rats by global ischemia contributed to regeneration of approximately 40% of the pyramidal neurons in this region, which survived at least up to 6 months after injury and were correlated with enhanced improvements in behavioral recovery in growth-factor treated animals133.

Endogenous augmentation of trophic factor expression (such as BDNF, NGF and FGF) in brains of laboratory animals has been achieved by behavioral interventions134 such as enriched experience, voluntary exercise135 and training/learning136. Both enriched housing and training have been shown to increase synaptogenesis132 and neurogenesis86 as well. In conditions of brain damage, environmental enrichment and physical exercise has been shown to have beneficial effects on the behavioral outcome of the injury irrespective of the origin and type of damage136,137 137. The protective effects of physical exercise were shown to be mediated by circulating IGF-I137. In most cases, the effects of enriched experience, physical exercise or training are thought to arise through activation of compensatory effects at the cerebral level.

The discovery of neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain has opened up avenues of research that will hopefully provide us with knowledge that will enable the development of therapeutic interventions to prevent and treat neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. Even though the gaps in our understanding of the neurogenic process are not insignificant, it is likely that continuing investigation into the basic biology of adult neural stem cells will allow us to modulate cell replacement processes in the adult brain. While efforts are devoted to the study of neural stem cell biology and the development of therapeutics126,127, it should be kept in mind that the contribution of adult neurogenesis to cognition is most likely a long-term process109,138. As behavioral interventions can stimulate neurogenesis in experimental models and possibly in humans, it is reasonable to suggest that lifestyle changes may constitute a therapeutic approach of low risk, albeit of variable efficacy, for the treatment of AD patients, particularly those at the early stages in the progression of the disease. Moreover, behavioral interventions may help societies increase their overall “cognitive reserve” and reduce the human, economic and social burden associated with increased numbers of cognitively impaired elderly in developed societies with high life expectancy. This goal can be achieved through the diffusion of knowledge, required for informed lifestyle choices, and the socialization of institutions providing access to continuing education, creative occupation, physical activity and the enjoyment of the arts.

1. Kuhn, H.G., Dickinson-Anson, H. & Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci 16 , 2027-33 (1996).

2. Kempermann, G., Kuhn, H.G. & Gage, F.H. More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature 386 , 493-5 (1997).

3. Maslov, A.Y., Barone, T.A., Plunkett, R.J. & Pruitt, S.C. Neural stem cell detection, characterization, and age-related changes in the subventricular zone of mice. J Neurosci 24 , 1726-33 (2004).

4. Pencea, V., Bingaman, K.D., Freedman, L.J. & Luskin, M.B. Neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and rostral migratory stream of the neonatal and adult primate forebrain. Exp Neurol 172 , 1-16 (2001).

5. Eriksson, P.S. et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4 , 1313-7 (1998).

6. Kukekov, V.G. et al. Multipotent stem/progenitor cells with similar properties arise from two neurogenic regions of adult human brain. Exp Neurol 156 , 333-44 (1999).

7. Selkoe, D.J. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298 , 789-91 (2002).

8. Mattson, M.P. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature 430 , 631-9 (2004).

9. Naslund, J. et al. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid beta-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. Jama 283 , 1571-7 (2000).

10. Masliah, E. et al. Altered expression of synaptic proteins occurs early during progression of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 56 , 127-9 (2001).

11. Terry, R.D. The pathology of Alzheimer's disease: numbers count. Ann Neurol 41 , 7 (1997).

12. Mucke, L. et al. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1-42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci 20 , 4050-8 (2000).

13. Hsia, A.Y. et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 , 3228-33 (1999).

14. Galvan, V.e.a. Reversal of AD-like phenotype in APP transgenic mice by mutation of Asp664. Submitted for publication. (2004).

15. Masliah, E. et al. Synaptic and neuritic alterations during the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 174 , 67-72 (1994).

16. Terry, R.D. et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer's disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 30 , 572-80 (1991).

17. Kuljis, R.O. Minimal cognitive impairment. in eMedicine, Specialties, Neurology, Behavioral Neurology and Dementia (2004).

18. Braak, H., Del Tredici, K., Schultz, C. & Braak, E. Vulnerability of select neuronal types to Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 924 , 53-61 (2000).

19. Gomez-Isla, T. et al. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 16 , 4491-500 (1996).

20. Davies, P. & Maloney, A.J. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2 , 1403 (1976).

21. Hawkes, C. Olfaction in neurodegenerative disorder. Mov Disord 18 , 364-72 (2003).

22. Mangone, C.A. [Clinical heterogeneity of Alzheimer's disease. Different clinical profiles can predict the progression rate]. Rev Neurol 38 , 675-81 (2004).

23. Peters, J.M. et al. Olfactory function in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: an investigation using psychophysical and electrophysiological techniques. Am J Psychiatry 160 , 1995-2002 (2003).

24. Koo, E.H. et al. Precursor of amyloid protein in Alzheimer disease undergoes fast anterograde axonal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87 , 1561-5 (1990).

25. Buxbaum, J.D. et al. Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor in the rat hippocampus: transport and processing through the perforant path. J Neurosci 18 , 9629-37 (1998).

26. Haass, C., Hung, A.Y., Schlossmacher, M.G., Teplow, D.B. & Selkoe, D.J. beta-Amyloid peptide and a 3-kDa fragment are derived by distinct cellular mechanisms. J Biol Chem 268 , 3021-4 (1993).

27. Vassar, R. & Citron, M. Abeta-generating enzymes: recent advances in beta- and gamma-secretase research. Neuron 27 , 419-22 (2000).

28. Weidemann, A. et al. Proteolytic processing of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein within its cytoplasmic domain by caspase-like proteases. J Biol Chem 274 , 5823-9 (1999).

29. Pellegrini, L., Passer, B.J., Tabaton, M., Ganjei, J.K. & D'Adamio, L. Alternative, non-secretase processing of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein during apoptosis by caspase-6 and -8. J Biol Chem 274 , 21011-6 (1999).

30. Lu, D.C. et al. A second cytotoxic proteolytic peptide derived from amyloid beta-protein precursor. Nat Med 6 , 397-404 (2000).

31. LeBlanc, A., Liu, H., Goodyer, C., Bergeron, C. & Hammond, J. Caspase-6 role in apoptosis of human neurons, amyloidogenesis, and Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 274 , 23426-36 (1999).

32. Galvan, V. et al. Caspase cleavage of members of the amyloid precursor family of proteins. J Neurochem 82 , 283-94 (2002).

33. Gervais, F.G. et al. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta precursor protein and amyloidogenic A beta peptide formation. Cell 97 , 395-406 (1999).

34. Chen, W.J., Goldstein, J.L. & Brown, M.S. NPXY, a sequence often found in cytoplasmic tails, is required for coated pit-mediated internalization of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem 265 , 3116-23 (1990).

35. Kamal, A., Almenar-Queralt, A., LeBlanc, J.F., Roberts, E.A. & Goldstein, L.S. Kinesin-mediated axonal transport of a membrane compartment containing beta-secretase and presenilin-1 requires APP. Nature 414 , 643-8 (2001).

36. Kimberly, W.T., Zheng, J.B., Guenette, S.Y. & Selkoe, D.J. The intracellular domain of the beta-amyloid precursor protein is stabilized by Fe65 and translocates to the nucleus in a notch-like manner. J Biol Chem 276 , 40288-92 (2001).

37. Matsuda, S. et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-interacting protein-1b/islet-brain-1 scaffolds Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein with JNK. J Neurosci 21 , 6597-607 (2001).

38. Scheinfeld, M.H. et al. Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) interacting protein 1 (JIP1) binds the cytoplasmic domain of the Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP). J Biol Chem 277 , 3767-75 (2002).

39. Taru, H. et al. Interaction of Alzheimer's beta -amyloid precursor family proteins with scaffold proteins of the JNK signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 277 , 20070-8 (2002).

40. Baek, S.H. et al. Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-kappaB and beta-amyloid precursor protein. Cell 110 , 55-67 (2002).

41. Cao, X. & Sudhof, T.C. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science 293 , 115-20 (2001).

42. Mattson, M.P. Cellular actions of beta-amyloid precursor protein and its soluble and fibrillogenic derivatives. Physiol Rev 77 , 1081-132 (1997).

43. Sprecher, C.A. et al. Molecular cloning of the cDNA for a human amyloid precursor protein homolog: evidence for a multigene family. Biochemistry 32 , 4481-6 (1993).

44. Wasco, W. et al. Identification of a mouse brain cDNA that encodes a protein related to the Alzheimer disease-associated amyloid beta protein precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 , 10758-62 (1992).

45. Zheng, H. et al. Mice deficient for the amyloid precursor protein gene. Ann N Y Acad Sci 777 , 421-6 (1996).

46. von Koch, C.S. et al. Generation of APLP2 KO mice and early postnatal lethality in APLP2/APP double KO mice. Neurobiol Aging 18 , 661-9 (1997).

47. Rakic, P. DNA synthesis and cell division in the adult primate brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 457 , 193-211 (1985).

48. Ramon y Cajal, S. Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System , (Oxford Univ. Press, London, 1928).

49. Altman, J. & Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol 124 , 319-35 (1965).

50. Altman, J. & Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. I. A longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis in some brain regions. J Comp Neurol 126 , 337-89 (1966).

51. Altman, J. Are new neurons formed in the brains of adult mammals? Science 135 , 1127-8 (1962).

52. Kaplan, M.S. & Hinds, J.W. Neurogenesis in the adult rat: electron microscopic analysis of light radioautographs. Science 197 , 1092-4 (1977).

53. Kaplan, M.S. Proliferation of subependymal cells in the adult primate CNS: differential uptake of DNA labelled precursors. J Hirnforsch 24 , 23-33 (1983).

54. Kaplan, M.S. & Bell, D.H. Neuronal proliferation in the 9-month-old rodent-radioautographic study of granule cells in the hippocampus. Exp Brain Res 52 , 1-5 (1983).

55. Gross, C.G. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma. Nat Rev Neurosci 1 , 67-73 (2000).

56. Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions , (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1962).

57. Lois, C., Garcia-Verdugo, J.M. & Alvarez-Buylla, A. Chain migration of neuronal precursors. Science 271 , 978-81 (1996).

58. Temple, S. & Alvarez-Buylla, A. Stem cells in the adult mammalian central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 9 , 135-41 (1999).

59. Bayer, S.A. 3H-thymidine-radiographic studies of neurogenesis in the rat olfactory bulb. Exp Brain Res 50 , 329-40 (1983).

60. Gage, F.H. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science 287 , 1433-8 (2000).

61. Alvarez-Buylla, A. & Lim, D.A. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron 41 , 683-6 (2004).

62. Sommer, L. & Rao, M. Neural stem cells and regulation of cell number. Prog Neurobiol 66 , 1-18 (2002).

63. Ohnuma, S. & Harris, W.A. Neurogenesis and the cell cycle. Neuron 40 , 199-208 (2003).

64. Doetsch, F., Garcia-Verdugo, J.M. & Alvarez-Buylla, A. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. J Neurosci 17 , 5046-61 (1997).

65. Alvarez-Buylla, A. Mechanism of migration of olfactory bulb interneurons. Semin Cell Dev Biol 8 , 207-13 (1997).

66. Anthony, T.E., Klein, C., Fishell, G. & Heintz, N. Radial glia serve as neuronal progenitors in all regions of the central nervous system. Neuron 41 , 881-90 (2004).

67. Alvarez-Buylla, A., Garcia-Verdugo, J.M. & Tramontin, A.D. A unified hypothesis on the lineage of neural stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci 2 , 287-93 (2001).

68. Lim, D.A. et al. Noggin antagonizes BMP signaling to create a niche for adult neurogenesis. Neuron 28 , 713-26 (2000).

69. Shen, Q. et al. Endothelial cells stimulate self-renewal and expand neurogenesis of neural stem cells. Science 304 , 1338-40 (2004).

70. Bedard, A., Levesque, M., Bernier, P.J. & Parent, A. The rostral migratory stream in adult squirrel monkeys: contribution of new neurons to the olfactory tubercle and involvement of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Eur J Neurosci 16 , 1917-24 (2002).

71. Bernier, P.J., Bedard, A., Vinet, J., Levesque, M. & Parent, A. Newly generated neurons in the amygdala and adjoining cortex of adult primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 , 11464-9 (2002).

72. Roy, N.S. et al. Promoter-targeted selection and isolation of neural progenitor cells from the adult human ventricular zone. J Neurosci Res 59 , 321-31 (2000).

73. Roy, N.S. et al. In vitro neurogenesis by progenitor cells isolated from the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 6 , 271-7 (2000).

74. Sanai, N. et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature 427 , 740-4 (2004).

75. Bedard, A. & Parent, A. Evidence of newly generated neurons in the human olfactory bulb. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 151 , 159-68 (2004).

76. Gould, E. et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult Old World primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 , 5263-7 (1999).

77. Kornack, D.R. & Rakic, P. Continuation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the adult macaque monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 , 5768-73 (1999).

78. Kempermann, G., Gast, D. & Gage, F.H. Neuroplasticity in old age: sustained fivefold induction of hippocampal neurogenesis by long-term environmental enrichment. Ann Neurol 52 , 135-43 (2002).

79. Shors, T.J. et al. Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 410 , 372-6 (2001).

80. Cameron, H.A. & McKay, R.D. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol 435 , 406-17 (2001).

81. van Praag, H. et al. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature 415 , 1030-4 (2002).

82. Hastings, N.B. & Gould, E. Rapid extension of axons into the CA3 region by adult-generated granule cells. J Comp Neurol 413 , 146-54 (1999).

83. Cameron, H.A., Woolley, C.S., McEwen, B.S. & Gould, E. Differentiation of newly born neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuroscience 56 , 337-44 (1993).

84. Dayer, A.G., Ford, A.A., Cleaver, K.M., Yassaee, M. & Cameron, H.A. Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol 460 , 563-72 (2003).

85. Leuner, B. et al. Learning enhances the survival of new neurons beyond the time when the hippocampus is required for memory. J Neurosci 24 , 7477-81 (2004).

86. van Praag, H., Kempermann, G. & Gage, F.H. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci 2 , 266-70 (1999).

87. Bayer, S.A., Yackel, J.W. & Puri, P.S. Neurons in the rat dentate gyrus granular layer substantially increase during juvenile and adult life. Science 216 , 890-2 (1982).

88. Grigsby, J.a.S., D. W. Neurodynamics of personality , (2001).

89. Deisseroth, K. et al. Excitation-neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron 42 , 535-52 (2004).

90. Squire, L.R. & Zola-Morgan, S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science 253 , 1380-6 (1991).

91. Kandel, E.R. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science 294 , 1030-8 (2001).

92. Gould, E., Beylin, A., Tanapat, P., Reeves, A. & Shors, T.J. Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Nat Neurosci 2 , 260-5 (1999).

93. Brown, J. et al. Enriched environment and physical activity stimulate hippocampal but not olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci 17 , 2042-6 (2003).

94. Rochefort, C., Gheusi, G., Vincent, J.D. & Lledo, P.M. Enriched odor exposure increases the number of newborn neurons in the adult olfactory bulb and improves odor memory. J Neurosci 22 , 2679-89 (2002).

95. Arvidsson, A., Collin, T., Kirik, D., Kokaia, Z. & Lindvall, O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med 8 , 963-70 (2002).

96. Mason, H.A., Ito, S. & Corfas, G. Extracellular signals that regulate the tangential migration of olfactory bulb neuronal precursors: inducers, inhibitors, and repellents. J Neurosci 21 , 7654-63 (2001).

97. Benraiss, A., Chmielnicki, E., Lerner, K., Roh, D. & Goldman, S.A. Adenoviral brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces both neostriatal and olfactory neuronal recruitment from endogenous progenitor cells in the adult forebrain. J Neurosci 21 , 6718-31 (2001).

98. Pencea, V., Bingaman, K.D., Wiegand, S.J. & Luskin, M.B. Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the lateral ventricle of the adult rat leads to new neurons in the parenchyma of the striatum, septum, thalamus, and hypothalamus. J Neurosci 21 , 6706-17 (2001).

99. Jin, K. et al. Neurogenesis and aging: FGF-2 and HB-EGF restore neurogenesis in hippocampus and subventricular zone of aged mice. Aging Cell 2 , 175-83 (2003).

100. Parent, J.M. Injury-induced neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. Neuroscientist 9 , 261-72 (2003).

101. Magavi, S.S., Leavitt, B.R. & Macklis, J.D. Induction of neurogenesis in the neocortex of adult mice. Nature 405 , 951-5 (2000).

102. Jin, K. et al. Enhanced neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease transgenic (PDGF-APPSw,Ind) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 , 13363-7 (2004).

103. Haughey, N.J., Liu, D., Nath, A., Borchard, A.C. & Mattson, M.P. Disruption of neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of adult mice, and in human cortical neuronal precursor cells in culture, by amyloid beta-peptide: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neuromolecular Med 1 , 125-35 (2002).

104. Haughey, N.J. et al. Disruption of neurogenesis by amyloid beta-peptide, and perturbed neural progenitor cell homeostasis, in models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 83 , 1509-24 (2002).

105. Wen, P.H. et al. Overexpression of wild type but not an FAD mutant presenilin-1 promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult mice. Neurobiol Dis 10 , 8-19 (2002).

106. Jin, K. et al. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 , 343-7 (2004).

107. Scarmeas, N. & Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve: implications for diagnosis and prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 4 , 374-80 (2004).

108. Snyder, E.Y., Yoon, C., Flax, J.D. & Macklis, J.D. Multipotent neural precursors can differentiate toward replacement of neurons undergoing targeted apoptotic degeneration in adult mouse neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 , 11663-8 (1997).

109. Kempermann, G., Wiskott, L. & Gage, F.H. Functional significance of adult neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14 , 186-91 (2004).

110. Shors, T.J., Townsend, D.A., Zhao, M., Kozorovitskiy, Y. & Gould, E. Neurogenesis may relate to some but not all types of hippocampal-dependent learning. Hippocampus 12 , 578-84 (2002).

111. Leavitt, B.R., Hernit-Grant, C.S. & Macklis, J.D. Mature astrocytes transform into transitional radial glia within adult mouse neocortex that supports directed migration of transplanted immature neurons. Exp Neurol 157 , 43-57 (1999).

112. Ullian, E.M., Sapperstein, S.K., Christopherson, K.S. & Barres, B.A. Control of synapse number by glia. Science 291 , 657-61 (2001).

113. Smit, A.B. et al. A glia-derived acetylcholine-binding protein that modulates synaptic transmission. Nature 411 , 261-8 (2001).

114. Oliet, S.H., Piet, R. & Poulain, D.A. Control of glutamate clearance and synaptic efficacy by glial coverage of neurons. Science 292 , 923-6 (2001).

115. Cullen, W.K., Wu, J., Anwyl, R. & Rowan, M.J. beta-Amyloid produces a delayed NMDA receptor-dependent reduction in synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 8 , 87-92 (1996).

116. Wu, J., Anwyl, R. & Rowan, M.J. beta-Amyloid selectively augments NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 6 , 2409-13 (1995).

117. Wu, J., Anwyl, R. & Rowan, M.J. beta-Amyloid-(1-40) increases long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol 284 , R1-3 (1995).

118. Stephan, A., Laroche, S. & Davis, S. Generation of aggregated beta-amyloid in the rat hippocampus impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity and causes memory deficits. J Neurosci 21 , 5703-14 (2001).

119. Kim, J.H., Anwyl, R., Suh, Y.H., Djamgoz, M.B. & Rowan, M.J. Use-dependent effects of amyloidogenic fragments of (beta)-amyloid precursor protein on synaptic plasticity in rat hippocampus in vivo. J Neurosci 21 , 1327-33 (2001).

120. Cullen, W.K., Suh, Y.H., Anwyl, R. & Rowan, M.J. Block of LTP in rat hippocampus in vivo by beta-amyloid precursor protein fragments. Neuroreport 8 , 3213-7 (1997).

121. Fraser, S.P., Suh, Y.H. & Djamgoz, M.B. Ionic effects of the Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid precursor protein and its metabolic fragments. Trends Neurosci 20 , 67-72 (1997).

122. Kim, H.S. et al. Carboxyl-terminal fragment of Alzheimer's APP destabilizes calcium homeostasis and renders neuronal cells vulnerable to excitotoxicity. Faseb J 14 , 1508-17 (2000).

123. Kamenetz, F. et al. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37 , 925-37 (2003).

124. Caille, I. et al. Soluble form of amyloid precursor protein regulates proliferation of progenitors in the adult subventricular zone. Development 131 , 2173-81 (2004).

125. Lopez-Toledano, M.A. & Shelanski, M.L. Neurogenic effect of beta-amyloid peptide in the development of neural stem cells. J Neurosci 24 , 5439-44 (2004).

126. Lindvall, O., Kokaia, Z. & Martinez-Serrano, A. Stem cell therapy for human neurodegenerative disorders-how to make it work. Nat Med 10 Suppl , S42-50 (2004).

127. Lie, D.C., Song, H., Colamarino, S.A., Ming, G.L. & Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: new strategies for central nervous system diseases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44 , 399-421 (2004).

128. Trejo, J.L., Carro, E., Lopez-Lopez, C. & Torres-Aleman, I. Role of serum insulin-like growth factor I in mammalian brain aging. Growth Horm IGF Res 14 Suppl A , S39-43 (2004).

129. Aberg, M.A., Aberg, N.D., Hedbacker, H., Oscarsson, J. & Eriksson, P.S. Peripheral infusion of IGF-I selectively induces neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 20 , 2896-903 (2000).

130. Lichtenwalner, R.J. et al. Intracerebroventricular infusion of insulin-like growth factor-I ameliorates the age-related decline in hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuroscience 107 , 603-13 (2001).

131. Carro, E., Trejo, J.L., Gomez-Isla, T., LeRoith, D. & Torres-Aleman, I. Serum insulin-like growth factor I regulates brain amyloid-beta levels. Nat Med 8 , 1390-7 (2002).

132. Carro, E. & Torres-Aleman, I. The role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor I in the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Pharmacol 490 , 127-33 (2004).

133. Nakatomi, H. et al. Regeneration of hippocampal pyramidal neurons after ischemic brain injury by recruitment of endogenous neural progenitors. Cell 110 , 429-41 (2002).

134. Mattson, M.P., Maudsley, S. & Martin, B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci 27 , 589-94 (2004).

135. Klintsova, A.Y., Dickson, E., Yoshida, R. & Greenough, W.T. Altered expression of BDNF and its high-affinity receptor TrkB in response to complex motor learning and moderate exercise. Brain Res 1028 , 92-104 (2004).

136. Will, B., Galani, R., Kelche, C. & Rosenzweig, M.R. Recovery from brain injury in animals: relative efficacy of environmental enrichment, physical exercise or formal training (1990-2002). Prog Neurobiol 72 , 167-82 (2004).

137. Carro, E., Trejo, J.L., Busiguina, S. & Torres-Aleman, I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates the protective effects of physical exercise against brain insults of different etiology and anatomy. J Neurosci 21 , 5678-84 (2001).

138. Shors, T.J. Memory traces of trace memories: neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and awareness. Trends Neurosci 27 , 250-6 (2004).

My thanks to Dr. Dale Bredesen and the Bredesen Lab for their continuous support, and to Dr. Alexei Kurakin for critically reviewing the manuscript and for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grant NIRG-04-1054 from the Alzheimer's Association and by the John D. French Alzheimer's Foundation